Bookish.com interviewed this great artist.

Find the original interview here :Bookish.com

Few adults have come of age without reading The Little Prince. The moving tale of friendship and loss is more than a captivating text; it is a near-religious experience for readers across the globe. As one of the world’s first mail-delivery pilots, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry worked tirelessly and fearlessly to connect people in his impossibly large world. Never could he have known that his most lasting impact would come in the form of this small book.

In between flights, he wrote often. Exupéry turned his fellow pilots into heroes through non-fiction works such as Wind, Sand and Stars, where he chronicles a harrowing journey of survival after a crash in the Sahara Desert. In the enchanting picture book The Pilot and the Little Prince, illustrator and writer Peter Sís gives due to the beloved author, depicting his life in a series of detailed and impactful images. We had the pleasure of sitting down with Sís to speak about his inspirations, the impact Little Prince first had on him, and the power of the picture book.

Bookish: When did you first read The Little Prince? What effect did it have on you?

Peter Sís: I’m not quite sure if I was 11, 12, 13, but I was living in Czechoslovakia. It wasn’t like we could really think about going places, so you would live all these adventures in books. And my father, (who) would give me books to read, came with The Little Prince, and he said, « This is a special book. » I read it, and it was amazing. I remember that it was about the promise that one day I would go and discover the world.

I read it again 20 years later, and again 20 years later. The second time I read it was with the illustrations; that was when I came to America to make a film in Los Angeles. At the time, I wasn’t sure: Should I stay? Should I go? Seeing it with the illustrations actually gave me fortitude. I thought, Well, he’s brave, and the pilot survives everything, so I will survive in America.

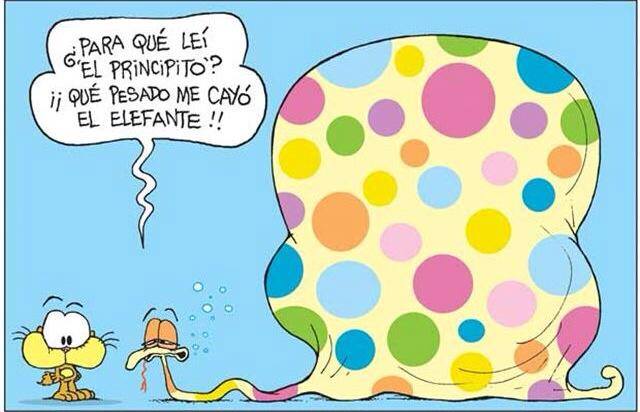

The last time I read it to my kids, I thought, Oh my God! This is so sad. I’m going to die now, too. But when I read it when I was 11 or 12, I didn’t see that at all. I saw: Wow, this is a cool way to travel. He doesn’t leave his body; it’s like his spirit is moving through space. It seemed more amazing.

Bookish: How did your readings of it influence the way that you wrote about Exupéry in The Pilot and the Little Prince?

PS: There’s a certain sadness to (The Little Prince), a melancholy. Exupéry says you cannot trust grown-ups. I think it’s also about how you see things as a child and how you see things, or read things, as an adult. That was difficult with this, to try to stay away from that melancholy feeling. I wanted to celebrate his life because he was this bigger-than-life man.

Bookish: When did you start the book?

PS: I wanted to do this 10 years ago. We were supposed to do a version of The Little Prince with U2, with Bono, that would go to Amnesty International. But I didn’t know how.

I would never dare to do Exupéry’s illustrations. His pictures have that feeling, that whole sentiment which gives the book its flavor. He wasn’t an artist who painted all the time. He did it with such an effort, there’s something heartbreaking [about that].

Bookish: What changed your mind?

PS: I was playing with it since then. Trying to come up with something, I went through his life. That’s when I realized he flies an airplane, then he crashes, he flies another airplane, and he almost drowns, he flies another… The airplanes were getting more sophisticated, but he would always break something or have stitches or almost lose his eye. In a way, I felt a lot like him. I’m very clumsy, too. I was always in the hospital with stitches.

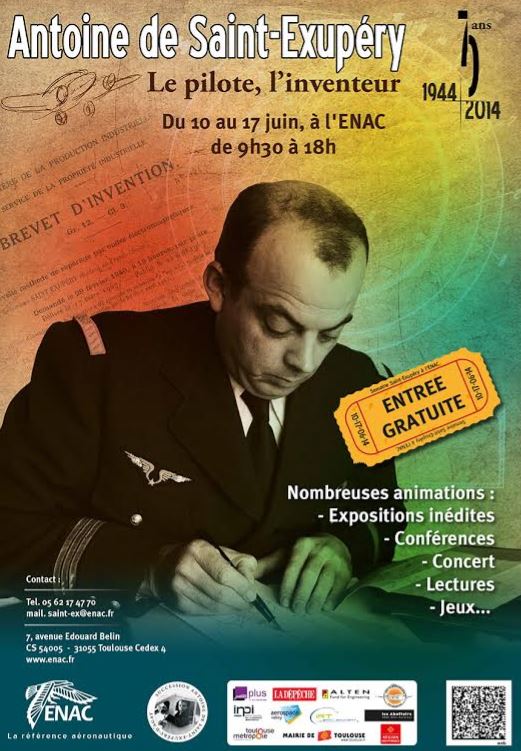

He also was a great inventor and a very smart man. Any time they would assign him to the company in the army, someone would say, « Oh it’s some idiot coming here » — because his family had this amazing, old aristocratic name. Then, he’d come and buy wine for everyone, play chess, all kinds of card tricks — they loved him.

He always became an essential part of any group he was in, to the point, that I think he had a problem then, because he wrote these books about how all the other pilots out there were heroes. He made them heroes in the public life — especially his friend Guillaumet, who was very shy and very private. He wrote a story about how Guillaumet walked through the mountains of South America for five days because he was afraid that if they didn’t find his body that his wife would not get the money from the company for him dying. Exupéry made Guillaumet into a hero in France. And Guillaumet is like, « I never wanted to be a hero. »

Bookish: The vibe I get from him, from your book, is that he did suffer — the crashes, horrible accidents, he dropped out of school, failed his tests — but there’s always a positivity about him.

PS: Yes! He’s very, very fond of life. Exupéry wanted to be a pilot and [he] became a pilot in the end, but many times it didn’t look like he was going to be anything. Everybody probably said, « Oh my God, he dropped out of school. What’ll ever become of him? » I like that page (of the book) in the sense that it shows what everybody is going through.

In a way, it’s also about me. I never thought I would be doing children’s books or books. I wanted to make films. I never thought I would be in America. It shows what you cannot tell the kids, like, « Hey! Don’t worry about it because you don’t know what will happen. »

Bookish: Exupéry crashed so many times. Was it difficult for him to overcome any fear and get back in that pilot seat?

PS: I think that’s the spirit of these early pilots. They’re amazing individuals that were, somehow, ready to die for it. Maybe sometimes when you get on the plane today, you have a little flash of I wonder if something will go wrong. But it’s a small percentage when something goes wrong. Their percentage must’ve been 75%. He definitely goes back, and it is shocking. I’m wondering if there were some people who said, « I will never go back because it’s insane. » But this whole being so brave, it’s one thing if you don’t get hurt, but he got hurt so many times and then he goes again.

They had the spirit of the pioneers. In the end, these four close friends who started in 1927, they all died in the air. Exupéry heard about his closest friend being shot down, that was just a tragedy of war. But nobody knows who shot down Exupéry.

Bookish: What do you think happened to him?

PS: They say that in these little planes sometimes the blue sky and the blue sea… that you don’t see the horizon, you lose completely the sense of… That’s what I always thought happened to Exupéry, that he didn’t know where is up and where is down, and he went into the sea. The only thing they know is they found the engine of the plane and his bracelet, which is in the (Morgan Library) exhibition and was given to him by his publisher.

There was a German pilot that said he shot him down. But they say the Germans had amazing, exact records of what happened each day, and there’s no record of shooting him down.

Another theory, which I have big problems with — some of the books claim that he was tired, depressed, and didn’t want to live, really. (They say) that he knew if he died, he would become bigger than life — that he had almost like a death wish. And I can’t say that he was happy. I can do it as an author, but I hate when people start to imagine what was the deep psychological state (of the person).

How does anybody know? I think it’s hard to write where it’s autobiographical and not make these innuendos.

—

This article was originally posted on Bookish.com